How To Grow and Heal After Experiencing Trauma

Can You Really Grow After Experiencing Trauma?

It’s a fact: experiencing trauma can shatter a person’s fundamental assumptions about themselves, others, and the world around us.1 If you’ve experienced trauma, you might know this firsthand – maybe you’ve questioned the role you play in broader society, noticed a shift in what you feel you can expect from other people, began perceiving certain events or experiences as unsafe, or experienced some other shift in thinking that changed how you navigate your daily life.

There is hope in the aftermath of trauma.

We know that humans have the ability to employ skills and strategies to remain functional, flexible, and generally “okay enough” in the face of stress, adversity, challenge, and change.2,3 You’ve probably heard of this concept: it’s called “resilience,” which is often referred to as the ability to “bounce back” following a traumatic or adverse event or experience.

There’s another possibility: Post-Traumatic Growth.

We know that humans have the ability to employ skills and strategies to remain functional, flexible, and generally “okay enough” in the face of stress, adversity, challenge, and change.2,3 You’ve probably heard of this concept: it’s called “resilience,” which is often referred to as the ability to “bounce back” following a traumatic or adverse event or experience.

How prevalent is PTG?

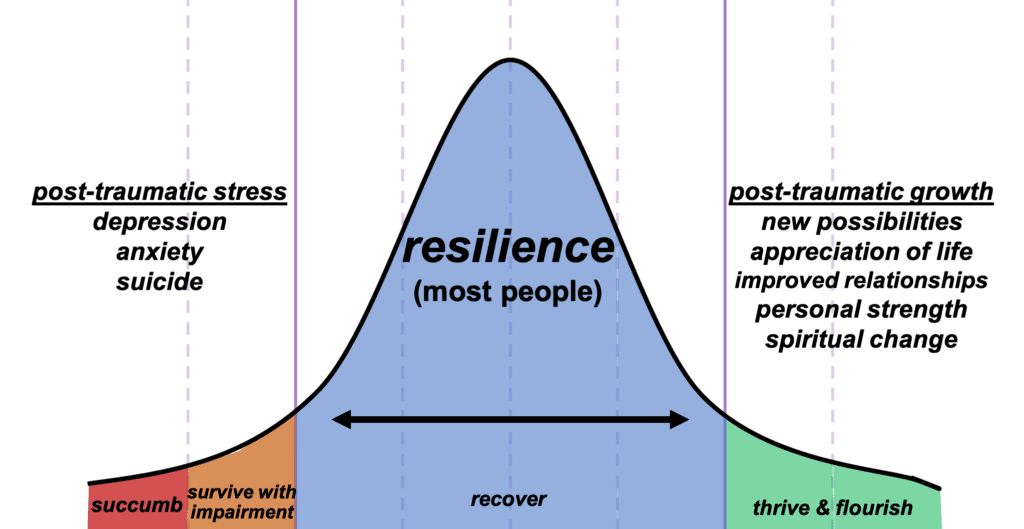

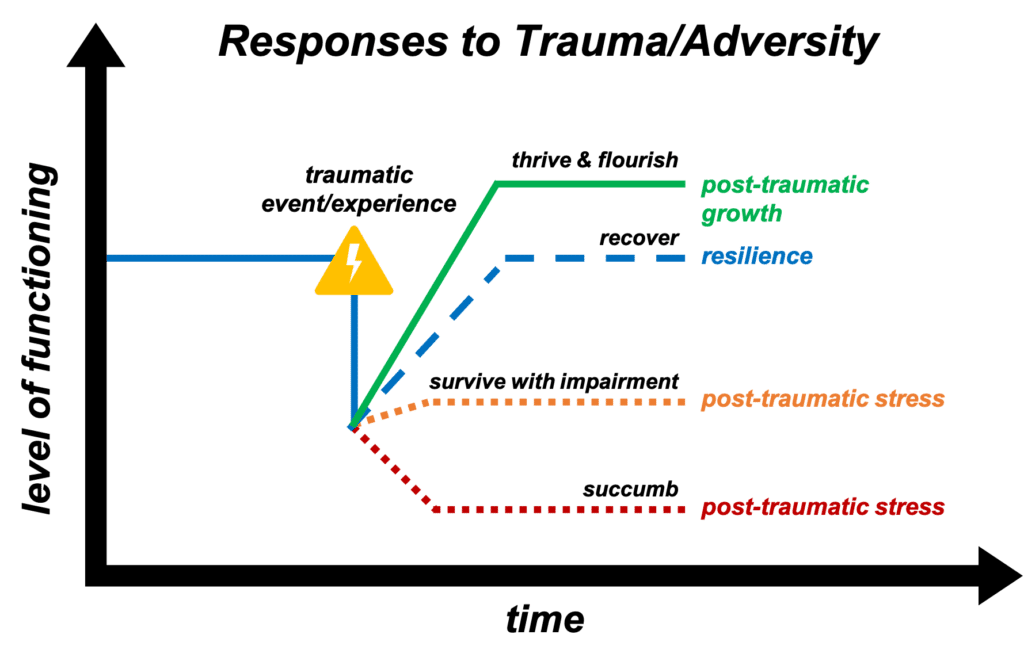

Not everyone who is exposed to trauma will experience the lasting, multidimensional changes in beliefs, aspirations, insight, and meaning that accompany PTG. The images below depict how PTG tends to show up as compared to resilience and post-traumatic stress.

Who can experience PTG?

With the right context and conditions for trauma recovery in place, PTG can be experienced by anyone who has been impacted by trauma. In fact, PTG has been reported across a broad and diverse array of individuals, including but not limited to those facing chronic, life-threatening medical conditions, those who have refugee experiences, those with a history of sexual assault and abuse, and those who have experienced the loss of a loved one.5,6

Wait—how exactly is PTG different from resilience?

Resilience is a personal attribute/quality that each of us has some level of, and we can each build skills and strategies to become more resilient over time so trauma and adversity feel more manageable when they come up for us. In contrast, PTG describes a process of transformation that takes a great deal of time, energy, work, and commitment to achieve following exposure to trauma that disrupts one’s view of self, other, and the world. That is to say: while resilience might help a person withstand and manage their reaction to future pain to some extent, PTG allows a person to harness the knowledge of using the hurt to change their lives in ways that bring them closer to their values and goals.

PTG doesn’t mean the path to trauma recovery is distress-free.

In fact, it’s quite the opposite! PTG and post-traumatic stress can (and usually do) coexist in the context of psychological struggles and suffering that inevitably emerge following recovery from trauma that is significant enough to disrupt a person’s sense of self-worth, beliefs about the broader world, and conceptualization of meaning in life.8 While most people who experience PTG would likely prefer not to have experienced trauma in the first place, making sense of an unfathomable event or overwhelming experience that happened can generate profound wisdom and insight, and noticing the signs of PTG can be an empowering, moving, and motivating experience along each person’s unique path to trauma recovery.5

PTG centers on your trauma recovery experience – not your trauma.

No particular characteristic(s) of a trauma event(s) spark PTG; it’s more about an individual person’s unique experience related to making meaning of navigating that trauma.4 And PTG is more than mere acceptance or acknowledgment that trauma transpired – PTG means mobilizing our strengths to redirect the pain (which may still be hurting) toward something that is more useful to growing and thriving as human beings than suffering and symptomology. Many items on Tedeschi and Calhoun’s7 PTG Inventory shine a spotlight on this connection by inviting people to rate their post-trauma alignment with statements such as: “I know better that I can handle difficulties,” “I am better able to accept the way things work out,” and “I am more likely to try to change things which need changing.”

Signs of PTG

There are five domains of PTG as established in Tedeschi & Calhoun’s7 seminal work:

- Appreciation of life – “I thank”

What it looks like: you are filled with new, enlightening aspirations, you have a will to really live that is stronger than before, and you anchor more readily in gratitude.

What wisdom is gained: to savor and celebrate the small joys in life; these moments are not to be missed or taken for granted.

- How it impacts the day-to-day: deeper contemplation for the value and meaning of life can lead to more intentional prioritization, deeper experiences of gratitude, more authentic feelings of compassion and empathy, and more embodied presence in the here-and-now.

An improvement in relating to and with others – “I cherish”

What it looks like: you experience a greater appreciation for and a strengthening of your close relationships with others, which themselves are much healthier, balanced, connective, and meaningful.

What wisdom is gained: humans are social creatures meant to be in community with one another, and you get to choose whom you do and do not let into your life.

- How it impacts the day-to-day: as you open yourself up to experiencing trust and a sense of belonging in relationships with others, you find yourself authentically opening up and courageously sharing more information about your own experience and perspectives.

The identification of new possibilities and/or a purpose in life – “I dream”

What it looks like: you see and seize new avenues for action that you may not have noticed or pursued before.

What wisdom is gained: the importance of connecting to and pursuing meaning and purpose in an ever-changing world in which new opportunities to support thriving continually emerge.

How it impacts the day-to-day: you pursue new, fulfilling paths with a greater sense of openness, flexibility, hope, and energy.

Greater personal strength – “I can”

What it looks like: you find yourself noticing your own capacity and skills more readily and authentically, which helps you stay in tune with your values and act in alignment with your aspirations.

What wisdom is gained: adversity and suffering are a part of the full experience of humanity, and you are able to learn to take care of yourself.

How it impacts the day-to-day: feeling more resilient and equipped to handle the blows in life that come your way, you are able to trust yourself to embody the wisdom and insight needed to safely explore life with a sense of curiosity and excitement.

Enhanced spiritual/existential development – “I accept”

What it looks like: you experience a sense of meaning-making that connects you with a sense of something greater than yourself.

What wisdom is gained: fully developed, meaningful beliefs and philosophies emerge and leave you feeling more connected to the world.

How it impacts the day-to-day: you notice yourself considering profound wonderments about life, death, and everything in between with fortitude, courage, and a deeper level of awareness.

“In some ways suffering ceases to be suffering at the moment it finds a meaning.”

Viktor Frankl, Man’s Search for Meaning

Factors that Make Post-Traumatic Growth More Likely to Happen

While the emergence PTG tends to unfold differently based on a variety of individualized and contextual factors, there are certain processes that have been identified as powerful catalyzers of PTG:5,6,9,10

- Knowledge is power!

Learning about how trauma and adversity can impact a person’s brain, body, worldview, and relationships is a vital first step in better understanding your own experience and more clearly seeing your truths on the pathway to healing, recovery, and growth.

Connection and community is key.

Speaking with others who have had traumatic experiences as well as confiding in trusted cared-for ones have both been shown to promote trauma processing, recovery, and PTG.

Process what happened, create a coherent narrative, and tell your story.

Although rumination tends to begin as an automatic, intrusive, repetitive, and even distressing experience, over time and with the support of others, as the trauma is processed, explored, and integrated into one’s full life story, your ways of thinking, knowing, being, and doing tend to become more organized, controlled, and deliberate, all of which is connected to PTG.

Therapy can be a critical tool to achieve the “forward bounce” of PTG.

There is evidence that suggests that people who choose to take their challenges to a professional therapist are more likely to cultivate PTG.

How Trauma-Informed Therapy Can Support You In Developing Post-Traumatic Growth

Without the right supports and tools, post-traumatic stress disorder and many other trauma-related impacts are much more likely to persist.10 Having someone to walk alongside you to provide support and guidance as you rebuild your assumptive world in your journey of recovery and growth can be a key factor in realizing PTG. In the face of ongoing suffering following trauma exposure, a therapist with an understanding about the nature of trauma as well as specialized training to address and heal the impacts of trauma can partner with you to more easily highlight and attend to the fertile ground for growth embedded within your experience.

Left: a broken bowl has been repaired by filling in its cracks with a lustrous gold lacquer. This is done in the fashion of the centuries-old Japanese artform of kintsugi, which showcases an object’s breakage and repair as an important part of its history that can ultimately make the object even more beautiful rather than as a blemish, flaw, or something to hide.

TL;DR

Trauma can indelibly impact us in ways that hinder day-to-day living, holistic wellbeing, and overall quality of and satisfaction with life. While most people are resilient and will be able to maintain some level of healthy functioning over time following trauma exposure, there are ways to surpass returning to baseline and to actually experience Post-Traumatic Growth. Trauma-informed therapy, such as EMDR and IFS, is one of the key tools that can help you tap into the deep reservoirs of strength, compassion, and humanity that you may not even have realized existed within you so that you feel more equipped to approach the inevitable challenges in life with a sense of curiosity, competency, and confidence

Authored by Whitney Marris

References

- Janoff-Bulman, R. (1989). Assumptive worlds and the stress of traumatic events: Applications of the schema construct. Social Cognition, 7(2), 113–136. https://doi.org/10.1521/soco.1989.7.2.113

- Garmezy, N. (1992). Risk and protective factors in the development of psychopathology. Cambridge University Press.

- Bonanno, G. A. (2004). Loss, trauma, and human resilience: Have we underestimated the human capacity to thrive after extremely aversive events? American Psychologist, 59(1), 20-28. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066x.59.1.20

- Woodward, C., & Joseph, S. (2003). Positive change processes and post-traumatic growth in people who have experienced abuse: Understanding vehicles of change. Psychology and Psychotherapy, 76(3), 267-283. https://doi.org/10.1348/147608303322362497

- Tedeschi, R. G., & Calhoun, L. G. (2004). Posttraumatic growth: A new perspective on psychotraumatology. Psychiatric Times, 21(4). https://www.psychiatrictimes.com/view/posttraumatic-growth-new-perspective-psychotraumatology

- Ramos, C., & Leal, I. (2013). Posttraumatic growth in the aftermath of trauma: A literature review about related factors and application contexts.

- Tedeschi, R. G., & Calhoun, L. G. (1996). The Posttraumatic Growth Inventory: Measuring the positive legacy of trauma. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 9(3), 455-471. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf02103658

- Zeiba, M., Wiechec, K., Biganska-Banas, J., & Mielezszenko-Kowszewicz, W. (2019). Coexistence of post-traumatic growth and post-traumatic depreciation in the aftermath of trauma: Qualitative and Quantitative Analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00687

- Forgeard, M. (2013). Perceiving benefits after adversity: The relationship between self-reported posttraumatic growth and creativity. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 7(3), 245-264. https://doi.org/10.1037/A0031223

- Jayawickreme, E., Infurna, F. J., Alajak, K., Blackie, L. E., Chopik, W. J., Chung, J. M., Dorfman, A., Fleeson, W., Forgeard, M. J., Frazier, P., Furr, R. M., Grossmann, I., Heller, A. S., Laceulle, O. M., Lucas, R. E., Luhmann, M., Luong, G., Meijer, L., McLean, K. C., … Zonneveld, R. (2020). Post‐traumatic growth as positive personality change: Challenges, opportunities, and recommendations. Journal of Personality, 89(1), 145–165. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12591